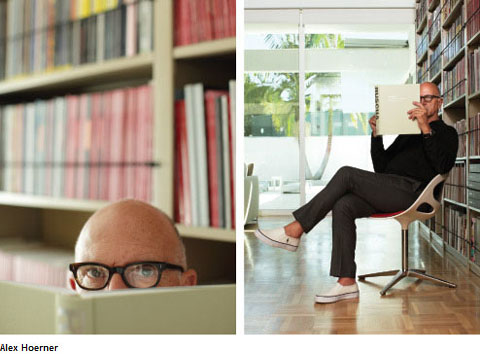

Michael Tuttle believes if you take care of fine books, they will return the favor

Maintaining private libraries seems a most unlikely career for the 21st century. After all, with iPads and Kindles, aren’t we on the cusp of change in how we experience the written word?

Maintaining private libraries seems a most unlikely career for the 21st century. After all, with iPads and Kindles, aren’t we on the cusp of change in how we experience the written word?

Michael Tuttle, who has carved a niche as a personal-library preservationist—an archiver/cataloger/appraiser, if you will—agrees, but with qualifications. He thinks the high-tech devices are great for newspapers, magazines and beach reads, but when it comes to first-edition literature, art and photography books, nothing can replace the real thing.

Tuttle has always had a passion for books. In the ’70s, he took a job selling them for Random House in northern Florida, in that long ago time before chain bookstores and Amazon, when sales were conducted in person, often with an author in tow. It was especially exciting in the South, with authors like Truman Capote, Tennessee Williams and Shelby Foote reading and signing at local bookstores.

Tuttle traveled with many of the greats, both the famous and the soon to be—like Maya Angelou, Alistair Cooke, Theodore Geisel (Dr. Seuss), James Michener and Julia Child. In those days, salesmen made little money, but the smart ones invested in their future (and fed their passion) by collecting autographed first editions. During this time, Tuttle started his own collection. In 1983, he left Random House and was briefly in business printing album covers and promotional material for music stores. Over the next two decades, he kept a hand in the medium he loved: printed materials of all types.

In 2005, Tuttle’s friend Glenn Goldman, who owned Book Soup in West Hollywood, said he needed someone to manage the Costa Mesa branch. And because of Tuttle’s printing experience, the pair planned to develop a line of books and cards. The printing business never got off the ground, but customers were always asking about getting their books repaired or covered. Friends continued to pick Tuttle’s brain about insuring and inventorying their books. Then his wife asked if he could choose to do anything, what would it be, and a light bulb went off: He would start a business taking care of books and libraries.

Most people who collect books don’t realize the value of their acquisitions, Tuttle says. Even those who don’t consider themselves serious collectors are surprised that ordinary books retain or go up in value.

Tuttle begins a job by inventorying a client’s books. He photographs each one individually and, depending on whether it’s signed by the author, begins researching what it’s worth, based on previous prices at auctions, stores and galleries. Clients receive a concise catalog of their collection to keep for reference. One of the more practical purposes is for insurance, as appraisers don’t typically inventory books.

“Some 50 to 60 percent of the value of your book is in the cover jacket,” Tuttle says, adding that the methodology for determining the value of a book often requires extensive research. For example, finding the value of a Gutenberg Bible is relatively easy because there are records of the prices paid whenever any of the very few copies are sold. But a more obscure volume—say, one of the books in the library of Judson Studios, which produced stained-glass work for such architects as Frank Lloyd Wright—requires far more time.

The value of an autographed book—referred to as an association copy—often depends on whose library it is part of. If James Beard, say, inscribed one of his books to Craig Claiborne, there’s an added value because both people are well known. And Tuttle’s services are particularly advantageous for clients who plan to leave their libraries to institutions. Knowing the worth of any literary collection solidifies the value of an estate.

Tuttle feels privileged to have access to both a range of amazing books and the people who collect them. Among his endeavors, he has created a library schematic for the arts, architecture and design books of restaurant impresario Peter Morton; worked with Policeman Andy Summer, who has amassed books on photography, the ’60s and the beginning of the English movement; categorized Brett Ratner’s assemblage of Hollywood publications past and present; and organized the library of Dede Gardner, who has been accumulating tomes on poetry and literature.

When asked about some of the more fascinating things he has come across, Tuttle recalls a paperback written in Spanish and signed by Argentine political icon Che Guevara. And while working for gallerist Niels Kantor—who inherited the library of his father, pioneering art dealer Paul Kantor—he came across a handwritten letter from Edgar Degas, as well as a spiral-bound, signed book by Man Ray.

Tuttle does have a couple of holy grails: a book from photographer Francesco Scavullo’s library, in which the photographer wrote disparaging remarks about Bruce Weber, was once on sale; and there was talk that photographer Horst’s collection included one with a diss of Richard Avedon.

In the meantime, he is encouraged that people are embracing the books they own and desiring to preserve them. The content may become available through electronic media, but Tuttle knows that the thrill of a book lies in not knowing what discovery might be made when you turn the page.

For information, you can reach Tuttle at matuttle.com